Ashes to Ashes

One of the services the boatmen of Scilly are often asked to perform is to scatter the ashes of the dearly departed.

Usually the family will have some idea of where they would like them scattered sometimes they are happy for the boatman to choose the spot. Of course, deciding on any particular spot will usually depend on wind and weather.

Such was the case, one Saturday afternoon when I was approached by a grieving widow, a lady I knew very well as both her and her husband, over the years had come out with me on the Swordfish many times. Having just arrived that morning, she was now searching for me.

I was standing near the ticket kiosk when she came up to me, I looked about but couldn't see her husband. "Hi there, where's the old man?" I enquired in a jocular fashion as I looked around.

"Back in the hotel room." Came the reply. "In an urn! I want you to take me out to scatter his ashes sometime"

I was struck dumb. But after my condolences and the shock of the news was overcome, we arranged a day to do the business.

The following Thursday, as planned I loaded her and her much reduced husband and off we set. I asked where she would like to scatter him but she didn't mind. He loved fishing and often went out with Alec fishing on the Southern Queen, so I suggested that as the wind was quite strong, from the Southwest, that the Hard Lewis reef (very good for fishing) in the Eastern Isles would be a good spot and wouldn't be too rough. She agreed, so off we went.

She had a friend with her and she asked that when she came to scatter the ashes she would like to do it alone, so I was tasked with the job of keeping the friend up the front with me while the ashes were scattered over the stern.

As we headed to the Eastern Isles I explained that when we got there, I would spin the boat around so we were head to wind and then she could scatter the ashes. I would give her the thumbs up when it was OK to do it.

20 minutes later, we were nearly there, I told her to take hubby back aft, hold on tight and stand by.

Off she went, stumbling and wobbling all over the place with the urn. I was worried that she might hurt herself so I slowed down considerably while she got to the stern. I was concentrating on keeping the boat as still as possible, but it was impossible. I asked the friend, who was watching her if she was there safely. So I could spin the boat around, knowing we would roll quite heavily for a few seconds. The friend, thinking she would just check, stuck a questioning thumb up. 2 seconds later, misunderstanding, the lid was off the urn, the ashes flung over the back and instead of disappearing behind us into the sea, the ashes came flying up past us and then a ghostly lady returned looking just how I imagined a ghost would appear. I looked back at the boat and it was also liberally covered. In my estimation, 10% went over the side, 25% was on the face and in the hair of wifey, and 65% remained in the Swordfish.

So the husband remained in the bilges, traveling around the islands for the next 13 years, all thanks to the friends thumb!

On another occasion a local family asked if I would take them out to scatter “Dad’s” ashes. I was, of course, pleased to perform this solemn duty. The day arrived, warm and sunny. They didn’t mind where he went, as long as it was “out in the tide somewhere.” I suggested just off Peninnis, on the south side of St Mary’s. All agreed.

Mum sat on the thwart beside me, holding Dad on her lap. As we passed the quay head and Rat Island, she suddenly stood up, went to the side, and plopped him in there and then.

“Ooh, he went down like a stone!” she remarked.

Two minutes later we were back at the quay, disembarking. Job done — the quickest scattering I ever did.

“Anyone want a wheel?”

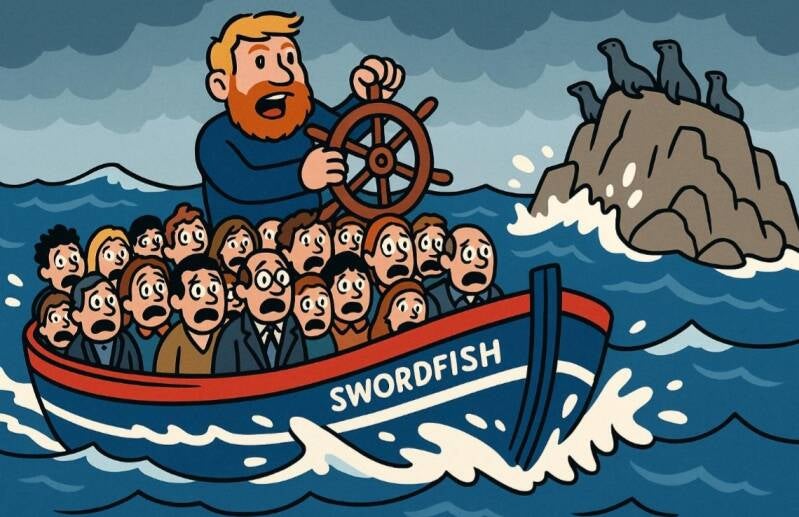

On one rough trip around the Eastern Isles, looking for seals, I’d gone round the back of Nornour and Great Ganilly where it was a bit calmer. We’d seen plenty of seals and were crossing to Menawethan when the sea turned choppy. The Swordfish was pitching and tossing, and I was standing, holding the wheel for balance — when suddenly it came off in my hands!

For a split second I was shocked, then I spun around, wheel in hand, and asked, “Anyone want it?”

The looks on their faces were priceless. Some laughed, some stared, and a few looked at me as if I’d gone mad. The wheel was quickly pushed back onto the spline, and off we went again — up and down as well as onward.

The Tyre Affair

One day, backing out from the steps at low tide, I managed to pick up a rubber car tyre around one propeller. There used to be plenty lying about on the seabed — old fenders from the Steamship Company’s launches Kittern, Tean, Gugh and the barges. When they fell off, no one bothered to retrieve them.

I was only heading to Lower Town, St Martin’s, so I carried on with one engine. All went well, but on my return I called in to the Harbour Master to report the problem. The tyre had cost me a bent propeller — about £100 — and I pointed out that the harbour floor was littered with them. He showed no concern and said I should be “more careful.”

I reminded him that the Queen Mother was due in two days, with a low tide on her arrival, and asked how he’d feel if her tender picked up a tyre and couldn’t stop, pitching her off her feet. He said it wasn’t his responsibility — only what happened on the quay.

“Fair enough,” I replied.

The next day, at low tide, I enlisted a friend with a tractor and trailer. We went down into the harbour and collected all the tyres we could find — thirty-two of them. I stacked the lot outside the Harbour Master’s office, blocking the traffic.

Beforehand, I’d popped into the paper shop to tip off Clive, the local reporter, that something was “going off on the quay in half an hour.” He arrived just in time.

Two minutes later, the Land Steward himself appeared, face like a beetroot. I was standing atop the pile, having my photo taken, while the Harbour Master tried to stay out of shot. A crowd had gathered.

“Right, in the office — now!” the Steward bellowed, pointing. The Harbour Master scuttled off, and I, hoping I was included, asked, “Did I hear a please?”

I swear I saw a vein pop in his temple.

Up in the office he began his dressing-down, but I interrupted to suggest he might first explain to his Harbour Master exactly which bits of the harbour he was responsible for — and then, perhaps, thank me for protecting the Queen Mum.

He spluttered, thought about it, and through gritted teeth said, “Thank you for clearing the tyres up.”

I turned to the Harbour Master, eyebrows raised, waiting. He mumbled something that sprayed the desk with spittle.

I decided the Steward had finished with me and made for the door — smirking, of course.

Seabird Specials

I always enjoyed the Seabird Specials while I was in the Boatmen’s Association. They were done on the high tide, when there was less sand or rock exposed and the birds gathered closer together.

When I first returned from my apprenticeship in 1975, I crewed for Dad, who ran the Seabird Specials. One day toward the end of the season, he told me there were a few Great Northern Divers about, and he hoped to find one.

Eager as ever, I kept my eyes peeled, scanning every bird in the sky. Standing amidships on the engine box, I suddenly spotted a magnificent bird flying straight toward us. Excitedly, binoculars fixed to my face, I pointed and yelled, “Great Northern Diver!”

Dad’s voice came back at once: “It’s a Great Northern Gannet, you fool!”

I stayed remarkably quiet for the rest of the trip.

The Shag and the Cormorant.

Some people, apparently, have forgotten the differences between a Shag and a Cormorant over the last 28 years since I last told them, so here is my lesson for this week in how to tell the difference.