6. New Beginnings

1980 arrived. All was good — the summer was warm and sunny, with lots of happy visitors. As the season wore on, we were looking forward to my sister Ann’s wedding on the 23rd of September. Dad made a couple of day trips to the mainland to be fitted for a new suit. He enjoyed the excuse for a day off and a change of scenery, but he wasn’t so sure about the suit itself. More than once I’d heard him mutter to a friend or two about the necessity of buying something he’d “only ever wear once.”

I was being allowed to skipper the boat more these days, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Vernie Hicks crewed for me whenever Dad was away, so I was learning a great deal from him too. I especially loved the round trips rather than just the direct runs. Every trip was different — the tide, the wind, the places to find birds and seals etc. (though they were always in the same general areas). And of course, there were always different passengers with different questions. I always told people that there was no such thing as a silly question, only silly answers. I’d heard Dad’s commentary so many times that I knew it off by heart and could give a running account of my own. Some found it annoying, but most enjoyed it — and thankfully the “enjoyed” outweighed the “annoyed.”

On the 29th of September, just a week after Ann’s wedding, we were on the Bryher direct trip with Dad at the helm. It was low spring tide. After landing a few people on Rushy Bay, Dad decided that instead of dragging slowly up the channel — bouncing from one sandbank to the next — to New Grimsby for a cup of tea, we’d nip around the back of Bryher. It would be quicker.

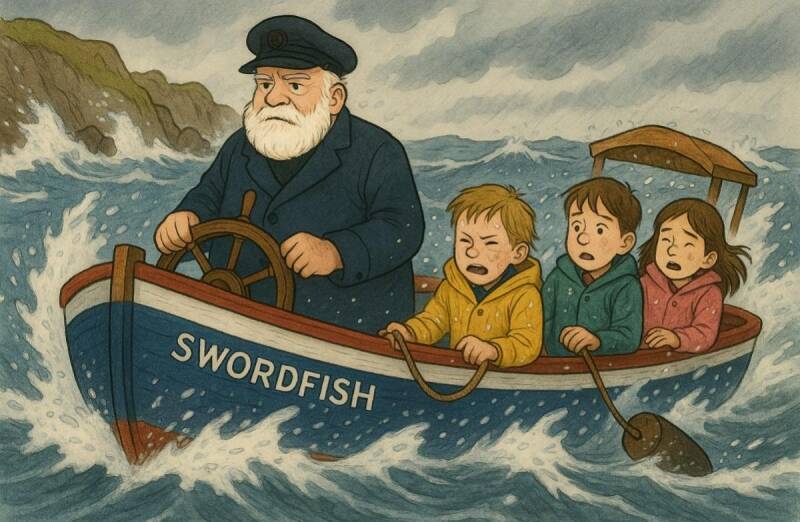

When we reached Hell Bay, I found out why it had that name. The wind was blowing stiffly from the north, with the tide running against it, so the seas were short, steep, and close together, coming at us from two directions. As we got into the thick of it, I was sent down to the stern to hang on to the punt's painter so that it didn’t snap. If we lost it, there’d be no turning back to retrieve it.

Meanwhile, Dad was working like a madman at the wheel and gear levers. The seas were confused — waves from the north, with others rebounding off the rocks from the southeast. If one caught us broadside, we’d have rolled. So Dad wrestled with the Swordfish: wheel hard to port, starboard engine hard ahead, port hard astern — then wheel hard to starboard, port ahead, starboard astern. Over and over for nearly three-quarters of an hour, until at last we found a lull north of Tresco where we could turn and run back into the channel.

It was the roughest sea I was ever in aboard the Swordfish, but I wasn’t worried. Dad was at the helm. Whether he was worried or not, I can’t say, though he was certainly concerned. All he said, on the way into New Grimsby for a silent cup of coffee, was:

“Christ! That reminded me of the time I was off Norway in the Navy, three days in a storm, barely making 3 knots into it to keep steerage. No one allowed on deck. When we finally came out, the railings, a lifeboat, and a gun had been ripped clean away.”

He said no more.

The next day he died.

The Morning After

The morning after Dad “popped off,” the sun shone, the sea was calm, but the island was heavy with grief. I decided it would help to take the Swordfish out alone, just to get the feel of things without him. My sisters Ann and Carol came too. We were going around St Mary’s, a nice quiet trip to face the reality of our loss. Quiet! I couldn’t hear myself think with all the wailing, so at Peninnis we spun around and went back to the moorings. The following day I was ready to return to work, and I took my first full trip to Bishop Rock Lighthouse without Dad. As we bounced alongside the tower I pointed out where the barque, ‘Fallkland’ had struck the lighthouse in 1901, leaving a scar half way up the side of it. I waited until everyone was looking up. Then I quietly slipped Dad’s thigh boots over the side, watching them sink into the deep blue depths.

--

The rest of the year passed with few problems, and I quickly settled into my new role as skipper — with the business side of things now also my responsibility. At the end of October the Swordfish was hauled up on to the bank at Porth Loo with the other pleasure boats. I stripped her down: engines, ropes, buoys, rafts, fenders — everything that moved went back to my garage to be stripped, cleaned, painted, and rebuilt over winter.

After Christmas, I started work on the boat itself. A huge 45-foot tarpaulin was tied over her like a tent, so I could work inside repairing woodwork, scraping paint, sanding, and clearing the bilges of the sand passengers knocked out of their shoes on to the floorboards where it all got washed into the bilges. (Bless them — though I wished they’d do it over the side!)

Working there in the depths of winter was always a trial, especially in the cold or when it blew a hooley. But by early spring the tarpaulin came off, and the Swordfish gleamed once again, pristine and painted. Then it was time for the outside hull, so by mid-March she was ready to be hauled back to the water for the new season to start on April 1st.

The very last job was always the worst: painting the bottom with antifouling. Like brushing on treacle. When Dad and I did it together, he handled the top half and cut the 'Straight’ line into the blue, while I lay on my back underneath doing the garboards and keel and getting dripped on from both brushes. I’d end up covered. At least now, doing it alone, I didn’t get covered quite as much — though it did take twice as long.

With the painting finished, I was sitting on a raft, beside the Swordfish having a coffee, when Roy Duncan came and sat, we chatted for a while. I told him that my favourite trip each year was the one where we launch and go from Porth Loo over to the quay each year. He smirked and said “Now it’s your boat, you’ll find that your favourite trip will be the last one from the quay to Porth Loo to pull the boat up each year!” I’m pleased to say that the first trip always remained my favourite.

Foggy Days

When Dad was teaching me how to navigate in thick fog, he had a rather brutal method. He would spread his oilskins over the windscreen so I couldn’t see a thing, then give me a compass course and the time I had to steam at 8 knots before altering course or slowing down. His wristwatch was placed on the deck beside the compass, and off we went.

At first, I struggled to get the hang of it, but gradually it sank in and trust in myself grew. Going from the quays back to St Mary’s was fairly straightforward, but being plunged into fog out at sea, with a course to be worked out quickly, was something else entirely. I never really enjoyed boating in fog—except for one unforgettable day in the mid-80s.

The Un-foggy day

The islands had been shrouded in dense fog for nearly two weeks, the only time I’ve ever known it to last so long. The Boating Association was restricted to short, direct trips. I felt sorry for holidaymakers who came and went without ever seeing the true beauty of Scilly—sunshine, blue skies, seabirds, seals, and the dramatic outer rocks.

One afternoon, I was doing the 4 p.m. pick-up from Carn Near on Tresco. About sixty people were aboard. I eased the boat astern from the quay, spun her around, and checked the compass bearing for St Mary’s. Suddenly, the atmosphere changed. I looked up, and before my eyes the fog began lifting—swiftly, everywhere at once.

In less than two minutes the islands lay before us in all their glory: St Mary’s, St Agnes, St Martin’s, Samson, the Eastern Isles, even Annet and the Bishop Rock Lighthouse. The cheers and clapping that went up were extraordinary. For those seeing the islands for the first time, after twelve days of fog, it must have felt like a miracle. It certainly did to me.

Uncanny Skills

The time I was most impressed by Dad’s ability in fog was one afternoon after we had landed passengers at Lower Town, St Martin’s. We had a couple of hours before the return pick-up, and Dad suggested we go catch some Coley (Poor man’s Pollock) for tea.

Now, I knew there were only a few spots he favoured for Coley—one being John Thomas Ledge, behind St Martin’s, well off Great Bay. The trouble was, visibility was down to about 150 yards, Round Island Lighthouse was grunting in the distance, and I thought Dad had lost his senses. How could he possibly find John Thomas’ Ledge in this?

But off we went. First Lion Rocks slid past us. Dad altered course, then altered again, then once more, seeing nothing.. Eventually he slowed, went hard astern, and said, “Right, lines over the side!”

Almost immediately we were pulling up Coley. Each drift over the ledge produced more. After four runs and a bucketful of fish, Dad simply said, “Right, we’d better go and pick these people up.” A few more course changes later, English Point appeared out of the murk, then Higher Town Quay. we'd passed by quite close to the Hard Lewis, Nornour and several other ledges and bits of rock and headland without seeing a thing.

To this day I don’t know how he did it. If I hadn’t been there, I’d have thought it a dream

Chay Blythe, lost in the fog

Another time, at the end of July 1971, we went out to find Chay Blythe as he passed Scilly on his solo round-the-world voyage in British Steel, heading for Southampton. Despite the thick fog, Dad and a few other boatmen in their pleasure boats steamed South into open waters to find him as he passed by

For two hours we circled around, searching in vain. Finally, after a few dolphins had joined us for a splash about in our bow wave and with no sign of the British Steel, Dad announced it was time to head for home. He turned north and calmly said that we’d come upon the Bow, the rock East of Gugh, in about forty minutes. and 'stap me vitals!' 40 minutes later he slowed the boat right down to a couple of knots, I sat on the foredeck, astride the stem post, eyes peeled for anything and everything from a rock in front of us to rocks and seaweed below us and within a minute or so the Bow emerged out of the fog. From there it was a few easy, short changes of direction and we were back home.

Spooky stuff!

Lesson Learned

I learned many lessons from Dad over the years and one lesson was: Never follow another boat in fog. They may not have their compass set correctly, or even know the correct bearings. Always trust your own compass, watch, and knowledge.

That lesson came back to me one day while returning from the Bishop Rock Lighthouse in fog. Another pleasure boat and I were heading back to St Agnes. He was about 3 minutes ahead of me. I set my course at 8 knots, watch beside the compass, and eventually came upon the Haycocks, then the Great Smith near Annet. I glimpsed the other boat ahead of us a couple of times, so I knew he’d reach St Agnes before me.

But when I arrived, there were people on the quay waiting for the boat back to St Marys. I asked why they didn't get on the other boat that came in a few minutes ago and they swore no boat had been in. The other skipper*, it turned out, had missed the Cow, missed the Kittern, missed Gugh and the Bow, and was wandering lost down the East side of the Gugh somewhere, between St Marys and St. Agnes. Dad’s words echoed in my head: Never follow another boat in fog.

*(He did eventually make it safely in to St Agnes, but I don’t know when as I thought best not to mention it to him.)

A Different World With Radar

It was a relief when we finally bought a radar. Life became much easier. But no radar could ever impress me as much as the way Dad could navigate through thick fog, as if he carried the whole chart of the islands in his head.

Dad never got to enjoy using a radar on The Swordfish. We didn’t have those until the early 1980s. What he did have, though, was the joy of a ship-to-shore radio, which made life so much easier and saved a lot of money.

Before radios, each boatman had to make strict plans about which boats were needed, where and when, to pick up all the passengers from the various islands, and stick to them religiously. Subsequently there was a lot of hanging around, waiting in case passengers wanted to return early. This often meant wasted trips, as perhaps only one boat was needed, but two were standing by. Once radios were installed, the pick-up arrangements became much more fluid. Boats could be called elsewhere if needed or stood down if not. There was also far less risk of overloading on the last trip home.

The radio also came in handy in other ways.

We were rolling and bouncing around beside the Bishop Rock Lighthouse one roughish day, side on to the rock. Dad was giving his commentary when a rather large wave suddenly washed over the rock that we weren’t expecting and a wall of water headed straight at us. Dad suddenly stooped down to the radio and fiddled with the controls for a second until the wave had rolled us around like a fair ground ride, peoples arms and legs flailing every which way. When the boat eventually came back upright, Dad stood back up, and said with a grin, “Christ, I thought that one was coming in!” and those of us around him had thought he was just adjusting the radio controls!

Oh! The fun we had!

Overloaded? Who, Us? Never!

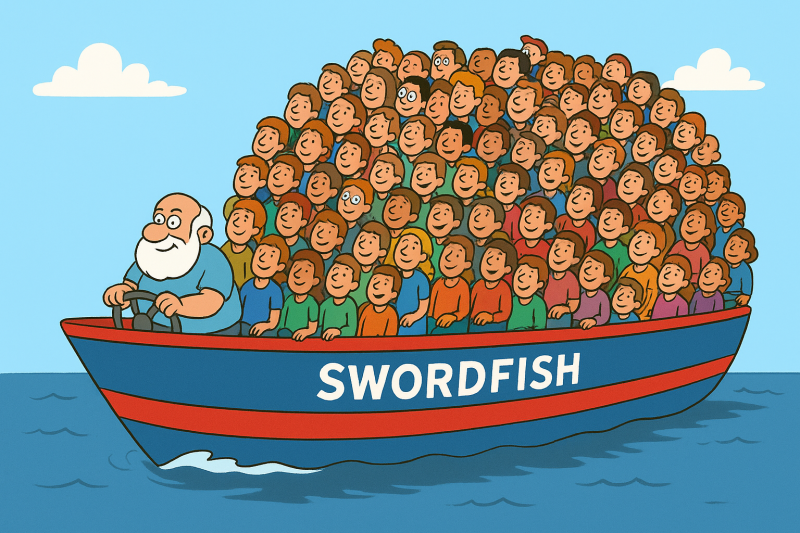

One afternoon, we were picking up the last few stragglers from New Grimsby, on Tresco. The weather was perfect, the sea flat calm, Thankfully. We had been told there would be about 63 passengers to collect, and The Swordfish was licensed for 72.

The customers came down the steps, and I helped them on board. They kept coming… and coming. Eventually, I had to stop them and point out to Dad that the boat was full — and there were still more people on the quay.

“Don’t worry,” he said. “It’s the last boat, everyone else is busy.”

It was August, and with all the children around, the boats often appeared to be only half full. So I let the rest on. The boat became so crowded that we had to put five passengers on the foredeck. Dad gave them a choice: under the foredeck or on top of it. They chose on top. I didn’t even bother collecting tickets that day; there was no room to move around.

When we finally reached St Mary’s, we counted everyone off. To our amazement, all 127 people were safely on board and none were left on the quay. Dad and I looked at each other in disbelief — clearly, one of the boatmen needed a lesson in counting!

That's it for this week folks More stories next week. Thanks for popping in.