4 - The Learning Curve

Christmas 1961 was one of my most memorable. Every year on Christmas Eve, we would be bundled off to bed with the threat that if we didn’t go straight to sleep, a certain be-whiskered, old fat man in a red suit wouldn’t come. But that year, I believe Dad spiked my Horlicks before I went to bed, as I really don’t remember anything after going upstairs.

I do remember being told I’d have to sleep in the spare bed in my sister Ann’s room so Santa could deliver the presents to both of us more easily. At that age, who was I to question it? I slept like a log, right through the night.

When I awoke, I found the pillowcase at the foot of the bed that Santa always left, full of all sorts of goodies. My squeals of delight and the noise I made ripping wrapping paper woke Ann. She immediately shot the bedclothes off herself and looked to the end of her bed… What? No pillowcase full of goodies for her. She looked bereft.

I made some wry comment about how she should have behaved herself better and gone to sleep quicker last night—then perhaps he would have left her something. That set off the tears: first a sniff, then a whimper, then a wail, and finally a full-blown breakdown.

Mum came rushing in to see what all the commotion was about, and when she realised, it didn’t take her long to get Ann to find her pillowcase, which had slipped over, under her bed and been covered by the bedclothes when she shot out of bed. Crisis averted.

Just then Dad appeared at the door, I thought ‘Oh hell! We’re in for it now!’ but he looked me straight in the eye, and said, “Have you seen what’s in your room?”

I replied that I hadn’t, and in my abject excitement—new toys, books, an orange, bars of chocolate, and torn wrapping paper were scattered to the four corners of the room—I rushed into my own bedroom. To my utter amazement, there stood a huge 8’ x 4’ plywood table with a fully functioning railway track, a train gently running around the double track (one inside the other but connected), pulling a couple of carriages. There were sidings, a signal box, a station, trees, figures of railway employees, another engine waiting to go on the tracks and lots of other details spread across the board.

I was gobsmacked! How on earth had Santa got that down the chimney?

I later learned that Mum and Dad had carried it up the night before and that Dad had spent most of the night setting it all up. It had nothing to do with Santa, I was shocked to the core! How Dad never woke me up I’ll never know—he had even drilled holes in the wall to fasten the table to it! I blame the horlicks!

.......

1962 brought a harder lesson. At the age of seven, Dad was rushed to the mainland one Sunday morning by helicopter after suffering a major heart attack. For nearly two years, I didn’t get to go boating very much at all. Life became rather serious.

I stayed with Auntie Ena in Auriga until Mum returned from the mainland with Dad. His recuperation was slow and difficult, but eventually he grew strong enough to get out and about again—walking greater distances each day until he was finally able to start work.

No one was more thrilled than me when he got back on the Swordfish II, as it meant I could go out again, learning the routes, rocks, and channels that were (and weren’t) navigable on certain tides.

This proved fortuitous, because when I was eleven the St Mary’s Sailing Club was reinstated, and soon I was able to put much of that knowledge to good use. The first meeting of the club was held in the old Wesleyan Chapel in Garrison Lane. About twenty-five people turned up, and it was decided there and then that the club should be revived. Very quickly, races began on Tuesday nights. The main boats were Redwings and Enterprises, although one or two other types occasionally entered the races.

Like many other youngsters, I was taught to sail in a Walker Tideway—a small but very solid clinker-built boat that was absolutely brilliant for learning. I can still remember to this day the wonderful sound of the waves lapping against the clinker hull as we gently glided forward over the water. Johan Hicks, from St Agnes was my sailing teacher. He certainly put me through my paces and so was thrilled when I was eventually allowed to teach others to sail too, a job I loved doing.

Over the following years Dad became the Commodore of the club, raised money with his Sunday night slide shows and bought 5 (if I remember correctly) Mirror dinghy kits, built them in our garage and painted them. They were used for teaching the youngsters and for racing in. I can’t say I ever enjoyed sailing Mirror dinghies as they were too small for me. After being used to sailing in the Aquilla (the Enterprise dinghy that Dad had built for himself when we first joined the sailing club) I couldn’t get used to having to fold myself in half in a mirror.

You can imagine my delight then, when Dad built a Wayfarer, larger than the enterprise. It was at that point I decided that I’d never get in a Mirror again, and didn’t.

I loved sailing, and on Tuesday nights I would crew for Dad in the Aquilla. We did reasonably well in the races, occasionally even winning one, but more often than not… we capsized! An experience I always enjoyed, and I think secretly Dad did too.

It was great fun getting the boat back upright, full of water. If we hadn’t pulled the sails down first, we’d be hanging on for dear life as the sails filled with wind again, the boat took off, and dragged us along with it—capsizing once more. Eventually, once we had it upright and ourselves aboard, we would sort things out, open the flaps in the transom, set a downwind course to pick up speed, and in no time the water would drain away and the boat was empty again. We could then re-join the race.

But Dad, ever the competitor, strove to win every time. He had no patience for laggards, lazybones, or loafers, and when we were sailing hard his commands were delivered with menacing military might. It wasn’t just his big bushy beard that commanded respect—though it certainly added to his presence—it was his vocal volcanic vibrancy, which carried for miles over the water.

Now, how do I know this, I hear you ask? Well, after one particularly frustrating race, when Dad was determined that this time we would successfully raise the spinnaker and win, nothing went according to plan. One disaster followed another, ending with the spinnaker wrapped hopelessly around the keel instead of flying proudly from the mast. Dad decided this was the perfect time to vent his spleen, which he did with great eloquence. (At this point I must point out that we never ever managed to get that confounded spinnaker up satisfactorily).

Later, when we got home, Joe Pender from next door—who had been on the golf links at the time—was laughing like a drain and proceeded to repeat every word Dad had uttered, complete with expletives. I was amazed, because we had been just off Nut Rock at the time, nearly two miles from the golf links!

That was when I realised from where I had inherited my voice.

When I was nine, I came home from school one day and Mum asked me who I had been shouting at during playtime. She then repeated what I had said to Rory Mckillan. I was stunned, because I hadn’t been shouting at all. She had been in the garden at the time, a full mile away from the school, and still heard every word…

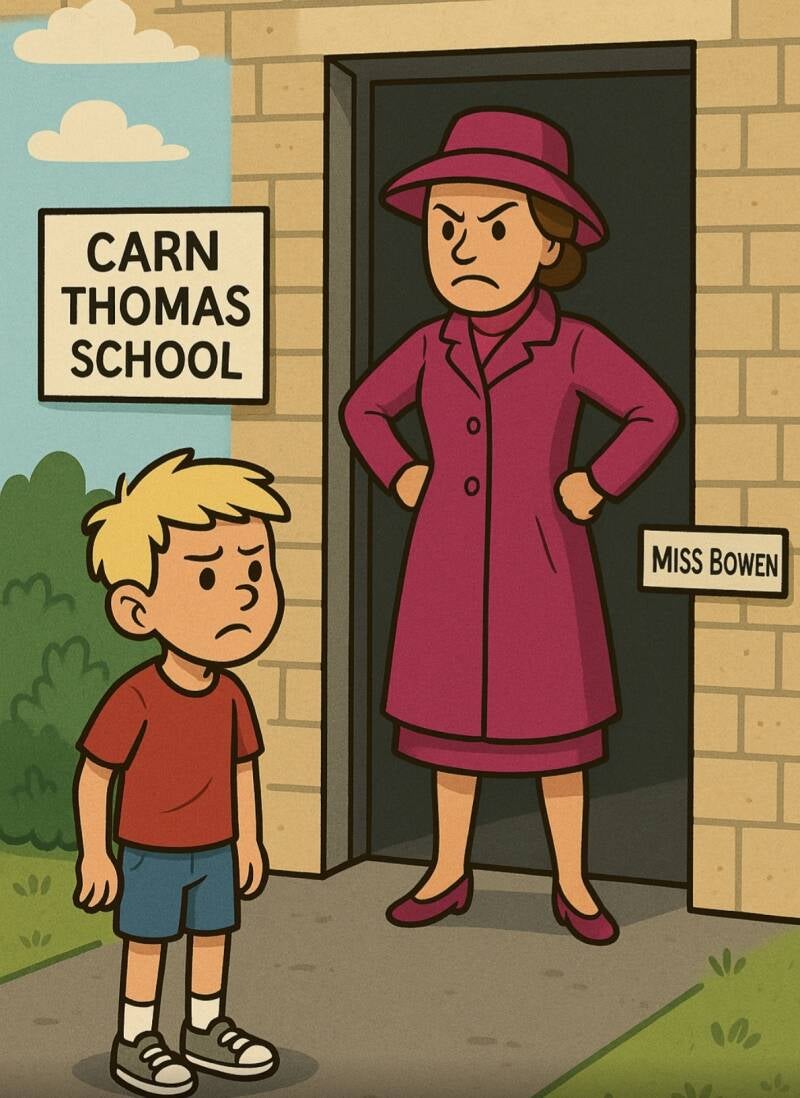

Another time, that had me flummoxed was during play time, we were up on the Carn; I was by the telegraph pole, (the one we were not supposed to go beyond) and I was explaining to one of my class mates the idiosyncrasies of our teacher, Miss Bowen, known as 'Fanny', to her juvenile charges! And upon the blowing of the whistle to tell us to hie back to class, 'Fanny' was standing by the door, arms akimbo, awaiting a full and detailed explanation from me as to why I thought it was a good idea to denigrate her in such a mean and miserable fashion! Another boll...... er.... telling off! I couldn't believe she heard me, when she had been down in the lower playground. Ooooops!

Another lesson that I learned from great experience, around the same time, was don’t knock people's heads against a granite stone wall, because there was such a thing as Karma! It all started in the playground again; this time I was having an argument with Rory and decided, foolishly, that it was time to take action, so as he was leaning against the wall by the double gates, I just pushed his head back against the stone behind his head. He winced, rubbed his head and sped off, just incase I was going to do it again! Well that sorted that problem I thought and went about my business for the rest of the day. Perfect!

A couple of days later I happened to find myself hanging around on the steps leading up in to the town hall, waiting for mum, when who should come beetling across the road from the hairdressers, but Katy McKillan (Rory’s Grandma), pinny flapping in the wind and with a face as dark as thunder. Without uttering a word, she rose the steps like a galleon in full sail climbing a mountainous wave, grasped me with both hands around my jowls, which I found a little disconcerting as I wasn't able to be my usual sweet self and smile at her like a little angel and she firmly bashed my head into the town hall wall. I'm sure the building shook with the force she used. I know I did. She spun on her heel, flowed back down the steps like lava from a spewing volcano and returned to her den of evil, her citadel of darkness, her quaint old hairdresser shop! She didn't need to say a word to me, I knew exactly what lesson it was that I had to get my head around, but that would have to wait a while until the throbbing had eased.

Unto this day, I still think the punishment was by far, more than was actually called for, but suffice it to say, I haven't ever bothered to knock anyone else's head against a brick wall!

Fortunately I never had to go to her again for a hair cut as just a few weeks earlier I had gone in for one and it was the first time I'd gone in on my own. I sat in her chair and as I'd seen someone come off the Scillonian a couple of days earlier sporting a very short hair cut that I thought was rather grand, I asked for a crew cut. She questioned whether my mother was happy about that. I quickly replied that she was fully on board with it and brandishing a shiny 2/6d I said "Look, she's given me the money to pay for it." So Katy gave me her finest rendition of a crew cut, and I certainly looked very American afterwards..... and then Mum saw me... yes, you've guessed it another dressing down! She also went in and gave Katy a piece of her mind too! So I think Katie's bashing of my bonce may have had something to do with that as well as Rorys knocked up noggin!

Oh well! We live and learn!

Growing up in Scilly was one of the greatest joys any child could have at the end of the twentieth century. With a safe, friendly, and caring community where everyone knew everyone, it was very easy to let your kids go off without a care. It was great for the children to have freedom — no mobile phones, nothing to keep you constantly connected to your parents. The only thing we all knew was that if we misbehaved, the news would get back to our parents before we did, through the “jungle telegraph.” Hopefully, it is still the same today.

From about the age of eight, we were generally allowed to go out on our own — meeting up with mates, swimming, fishing, building treehouses, and a myriad of other things that would occupy our hearts and minds.

I think the worst thing we very occasionally got up to was scrumping. My favourite place for that innocent pastime was up by Argymoor duck pond. There was a lot of “icing” on the walls opposite the turning into Trenoweth, in the middle of Pungies Lane, which was great for clambering around on, but on the other side of the road was an orchard.

One day, three or four of us were playing on the icing when it was decided that we should avail ourselves of some Cox’s Orange Pippins. Well, you can guess who was voted the “ideal” person to pop into the orchard to purloin a few while the others stayed on the wall to receive the stolen apples. Well, I hadn’t been in the orchard more than about seven seconds when a voice behind me said, “And what do you think you are doing?”

I turned and saw “Fanny” standing a few yards away. I was so horrified that, with one deft leap, I was over the wall and gone. I don’t think I stopped running until I got to Telegraph Tower, puffing and panting like a tatterdemalion traction engine. I tried to convince myself she didn’t recognise me, but who was I fooling? First thing on Monday morning she wanted chapter and verse on why I thought I could steal someone else’s apples. My only excuse? Because I was very hungry!

At the age of thirteen, a very kind lady, Joan Beale — a house mother from Mundesley, the school hostel — gave me an 18ft “jolly boat” called Echo. She owned it but could no longer use it. The Echo, built by Mr. Wilfred Phillips, was a replica of the original jolly boat 'Wizard', designed by Group Captain Burling and Uffa Fox, which I later discovered was residing in the boathouse at Porth Mellon along with Group Captain Burling’s yacht Spiro.

The Echo was a very fast three-man sailing dinghy. It was fitted with an extremely heavy keel — the bottom half made of solid lead — and it needed a pulley system to raise and lower it. It had a 32-foot mast with a large expanse of sail to match. The boat was very lightly built, carvel-designed with thin ribs holding the planks together. It was so delicate that if I stepped off the floorboards onto the ribs, I would snap them and cause the boat to leak. Great care was needed when moving around inside.

Dad decided the Echo was more than a thirteen-year-old lad could handle, so he fitted a 22ft Wayfarer mast and sails, built a foredeck, removed the lead keel (which he melted down to make a great many fishing weights), and made me a plywood keel that I could operate on my own.

With Echo now much lighter, it was easier to haul her up and down the beach on a trolley when I wanted to go sailing. But I still, I couldn’t manage pulling it up on my own, so Jimmy Williams, the harbour master, allowed me to drop a mooring near the Lifeboat slip allowing me to keep her afloat.

I spent a great deal of my time sailing after that — with or without crew. I was in my element. Of course, with Echo being moored in the harbour, I had to use a punt to get out to her. I kept this on a running line just below Holgate’s Hotel and one day, as I rowed back after a sailing 'adventure', I noticed Group Captain Burling standing at the top of the steps into his garden of Holgates, beckoning me with a bony finger. It was the first time he called me over. We chatted for a few minutes, and as the summer wore on, he often invited me over. Eventually, I was shown his Rolls Royce — kept in the hotel kitchen! (It is now in the Beaulieu Motor Museum in Hampshire.) He also showed me around the hotel and many fascinating relics from his Air Force career. He was certainly a very interesting chap.

Anyway, I digress. I loved Echo and entered the weekly sailing races, but because she was bigger and faster than the others, I always ended up miles ahead on my own, which I didn’t enjoy so much. More often than not, I abandoned the race halfway and went back to join the others — usually getting in their way, much to their chagrin.

I had many adventures in Echo and learned many lessons. Two of the best came after a jolly jaunt with my sister Jane to St. Agnes. With a north-easterly breeze, the trip over was fast and exhilarating. But the wind had risen, and on the way back to St. Mary’s we found ourselves beating into a stiffer breeze, against the tide, and in seas that were far too big for our comfort. Spray flew, we were soaked to the skin, and progress was slow. Then who should appear but Swordfish II, heading our way. Dad had spotted us as he returned from Samson and decided to escort us home.

I thought I was in for a rollicking, but when we landed safely, all he said was: “Next time, listen to the forecast. Always listen to the forecast. And when you go out, do the hard part first so coming home will be easy.” In other words: beat upwind first, so when you are tired and worn out, the return journey will a pleasant downwind run. I always remembered that — and still pass it on to others.

One of the problems with keeping Echo on a mooring was that she filled with rainwater and often needed bailing. Many times after school I’d have to go out and empty her, much to Mum’s annoyance when I returned in wet and sandy school clothes and shoes, yet again. After discussions with Mr. Parker, our wood and metalwork teacher, I built a clever little gadget to solve the problem. It worked on the movement of the waves: a float bobbbed up and down, moving a piston with a simple valve. The downward stroke let water into a chamber, the upward stroke lifted it out of the tube while drawing more from the bilge. Brilliant! It kept Echo dry without me having to dash out every time it rained. The pump was a great success until I went out one day and found it had gone. Was it stolen, did I not tie it correctly or did the rope break! Who knows? Not I!